Decentralization to Centralize Human Thought & Universalize Access to Knowledge

5:30p 2015-11-30 Mon

Read original post on Facebook

Abstract

Over the last three years, we've seen a lot of movement around what people are referring to as the "Decentralized" or "Distributed" Web. It's often accompanied by words like "blockchain", "cryptocurrency", "content-addressability", "P2P" (peer-to-peer), "torrents", "mesh", and protocols/implementations like ipfs, dat, secure scuttlebutt, gun, and solid. What's the deal?

In the 1960's, 20 years before the Internet even existed, Ted Nelson was presciently describing a system called Xanadu which featured unbreakable bi-directional hypertext links, version controlled documents which supported incremental publishing, and side-by-side document comparison. By 1991, when Tim Berners-Lee invented the World Wide Web, only a subset of his and Ted's ideas made it mainstream. Now, after 25+ years of learnings, its become clear we didn't get everything perfectly the first time around. Some of these compromises and shorcomings were imposed on us through limitations in technology. Advancements in cryptography, computer networks, web standards, and computing power have since unlocked possibilities which were out of reach the first time around.

With Ted Nelson and Tim Berners-Lee at the Internet Archive for the Decentralized Web Summit 2018

Hindsight is twenty-twenty. The "Decentralized Web" is an effort to redesign elements of the World Wide Web which revealed themselves to be imperfect and to integrate concepts which were previously too expensive or complex to operate efficiently at scale. For instance, much of the web isn't backed up anywhere and there's only a single copy. If this copy disappears, its lost for good. Also, web sites change over time, often clobbering their previous versions because the web doesn't have version control. Tons of content on the web is duplicated in inefficient ways. The current web user is at the mercy of ISPs to route them to content, which means it would be easy for an ISP to censor information they rely on. The web isn't currently designed for offline access. While we have protocols like bittorrent which allows users to share the load of transfering files, the web wasn't built to work this way.

But as is any topic of digital warfare, the drive for a Decentralized Web is not all sunshine and roses.

Table of Contents

- What is the web?

- Evolution of the Web

- Centralization, Decentralization & Re-Centralization- Breaking the Cycle

What is the World Wide Web?

We should probably start with one of the most common conflations: that between the Internet and the Web (because for many, these two technologies are effectively synonymous).

In 1961-1965 computer users were less concerned with sending messages between computers and more concerned with communicating with the other handful of users who were time-sharing multiplexed central mainframes with them. To communicate with each other, they would create files with names like "TO TOM" and place them in public folders. Noel Morris and Tom Van Vleck ran with the idea to create the MAIL program, which MIT supported because they needed away to alert people when their processes had finished running. Mail will become an important use case later in this story.

The early Internet began circa 1969 with the ARPANET network, a project funded by the US Department of Defense. One of project's first victories was a packet switching node called the Interface Message Processor (IMP) which enabled participants to interconnect within the ARPANET network. Fun fact, IMP was the topic of the first RFC-1 by Steve Crocker. In June 1970, RFC 54 was published detailing a new protocol called the Network Control Program which allowed two computers to connect on 2 seperate ports (a dedicated channel for each machine to receive and send, respectively). In 1971, Abhay Bhushan built the File Transfer Protocol (FTP) on top of NCP and made it possible and easy for computers to implement and participate in file sharing. Shortly after in 1972, Ray Tomlinson combined his bespoke CPYNET file transfer program (which Bhushan discusses in RFC 310) with SNDMSG to send the first email. By ~1976, email accounted for 75% of all ARPANET traffic and the idea of networked computers was catching on.

"Our experience with ad hoc techniques of data and file transfer over

the ARPANET together with a better knowledge of terminal IMP (TIP)

capabilities and Datacomputer requirements has indicated to us that

the Data Transfer Protocol (DTP) [...] and the File Transfer

Protocol (FTP) [...] could undergo revision. Our effort in

implementing DTP and FTP has revealed areas in which the protocols

could be simplified without degrading their usefulness."

(source)

The Internet as we know it today took shape in 1983 when Robert Kahn and Vint Cerf, ARPANET engineers, co-invented the TCP/IP stack which deprecated NCP and provided a new generalized a common interface for multiple computers to address, connect, and transmit information to each other. One key advantage is it only required binding to one duplex port (for sending and receiving), whereas NCP bound to two simplex ports. The IP part of TCP/IP allows each computer to have its own uniquely identifying Internet (Protocol) Address (similar to a street address). Any machines with IP addresses could follow the format of TCP to request and establish a connection with others. When you are downloading a linux distribution using bittorrent, you are using the Internet and taking advantage of the TCP/IP stack but you are not using the web (unless you found the torrent magnet link via a website). IRC protocol and AOL Instant Messenger (AIM)'s TOC2 would have been two other examples of services which required Internet access and TCP/IP connections but operated independently of the web.

Me and Vint Cerf at Internet Archive's Innagural Decentralized Web Summit in 2016

By the late 80s, the groundwork -- i.e. many of the protocols we still use today -- was in place, but the Internet was being used in one of two ways. First, computers were connecting directly to each other to transfer files from the command line and second, groups were creating an array of bespoke protocols on top of TCP/IP to enable specific uses cases like mail and chat (IRC). So what was missing?

For one, in the spirit of mailing, there wasn't a good way to make your messages public to everyone. Sharing was really hard. Tim Berners-Lee envisioned an ecosystem which enabled, "automatic information-sharing between scientists in universities and institutes". With FTP you were very limited in what you could show other users -- they could essentially only download or upload raw files, not seamlessly navigate documents.

The web was conceived in much the same way as mail was at MIT. Ted Nelson originally demo'd hyperlinks as a way for jumping and navigating documents locally in his Xanadu system, even though his bigger picture was to allow hyperlinking across computers.

In December 1990, Tim Berners-Lee created a new type of service which would make the idea of the web mainstream by releasing the first HTTP server: CERN httpd. The idea was, anyone in the world could install an HTTP server on their computer and, so long as the server was running, it would become part of a global network of documents which could be accessed by a new type of address called a URL. Shortly after in 1993, special document viewers called web browsers were born which were able to any person's published documents who was running and http server. This was only possible because many people were running the same software and all the machines were speaking a common language which these web browsers were programmed to speak.

Evolution of the Web

This isn't the first time the Web has sought to evolve. We've seen an important drive every 7 or so years. In 1999 there was an effort labeled Web2.0 "The Participative / Social Web" which was a drive to make the Web more social and to empower participation. During this period, websites started to become much more dynamic with the use of javascript. Social networks emerged where conversations and commenting became mainstream online.

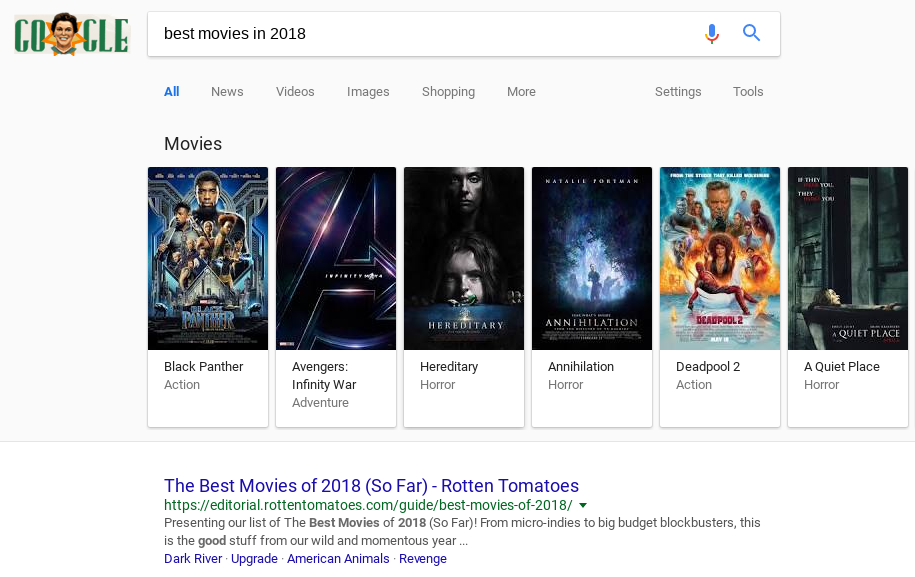

In 2006, we launched into Web3.0 "The Semantic Web", an effort which urged website creators to enrich/annotate their website content with additional semantic metadata to make it more searchable and discoverable. The inclusion of this metadata is part of what allows google and other search engines to show smart results when you type in a query like, "best movies in 2018".

A search for "best movies for 2018" in google returns smart, zero-click, Google Now results powered by their knowledge graph

Between 2011 and now we've seen a variety of important technologies emerge. Javascript build systems and transpilers, React and Angular, single-page-webapps, progressive web apps, polyfills and web components, flex & grid. But more than anything, what we've seen is concentration of power. Google acquired youtube in 2006. Verizon acquired Yahoo and AOL. Facebook owns instagram and whatsapp. Microsoft now owns linkedin, yammer, github, and skype and also has a 11.5% stake in Comcast and 3% of AT&T. During this period google, facebook, youtube, twitter, instagram, pinterest, nytimes, soundcloud, dropbox, archive.org have all experienced blockages from China. In 2017, the United States Federal Communications Commission (FCC) passed a vote on Docket 17-108 to roll back the Open Internet Order of 2015 which makes it so US Internet Service Providers (ISPs) can offer preferencial treatment (e.g. fast-lines) to the competing web services they own and manage. And the web has become rampant with companies who use supercomputers to play "chess with your mind" and inundate our attention with advertisements. In one sentence, the world wide web is starting to look a lot like cable tv and engineers and activists alike are beginning to look towards changes which may require a fundamental paradigm shift in how the web works.

How the Web May Be So Much More

The World-Wide-Web is no longer a "web", but a collection of fragmented, sparsely-linked Webs in competition. Individual services are filling the gaps that the Web is not. And it's a huge missed opportunity; a re-inventing the wheel.

The World-Wide-Web is one of the most valuable things we (as a society) have. Tens of thousands of people have tried to create their own "webs" of knowledge (edu websites, google docs, papers, books). Millions of resources of become link-rot, have never been discovered. Some networks, like Wikipedia, have flourished by becoming their own essential sub-webs which focus on, e.g. encyclopedic information. They follow strict guidelines and keep the experience and format as simple as possible so they can focus on accessibility and improving quality. But even with concerted efforts like this, millions of web pages fail to actually be apart of any meaningful "web" (outside of perhaps appearing on a google result page, or resolving if you happen to know the url).

Hundreds of millions of people view web pages in their browser. Their thoughts about the quality of the web page or its usefulness die when we leave the page. The content we view is rarely backed up offline or cited and republished in a useful way.

Facebook, twitter, and other networks have been following Wikipedia's example in building a "Read-Write Web". They are making it easy -- easier than Wordpress -- for everyone to have an instant voice; their own coherent web of comments. It's enabled everyone to be apart of the Great Conversation, complete with filters (lenses) to see each contributor's person journey (web).

One of the most interesting 1-liners I heard Brewster Kahle (founder of Internet Archive) say was, "Twitter is actually just annotations for the web". And it's so true. Twitter allows patrons to democratically create links to resources which may otherwise languish in obscurity.

"That which is not tied on will be lost"-- Ted Nelson (2018-06-16)

Twitter, even more than facebook, has enabled the community to provide *context* to the web. If Wikipedia is the world's democratic encyclopedia, Twitter is the world's way of democratically bringing/linking content into our web.

In my humble opinion, facebook and twitter have become shining examples of solutions, which miss the most important problems they could be most impactfully solving. Right now Facebook is used predominantly for social connection. It's not used for enabling the world to refine a more useful web.

Science is fragmented. Methods and results are not shared. Or if they are, they're published in different formats. There are few "social" networks which enable curation and collaboration of e.g. science because they are expected to be "social" (w/ all the features and distractions that come with this classification).

What the world needs is a web with twitter built-in. Not twitter, the service. And not an "annotation" specification. But a web that intelligently grows as people use it. A web that's able to connect itself.

When I visit a web-page, this should have an impact on the web. If a page is viewed or cited, it should be backed up somewhere. As a web page changes, there should be some history of these changes. And we should be able to link to these changes. If someone bookmarks a page, this information should be anonymized and contribute to something like "page-rank". One should be able to *query* the web to discover implicit/inferred links (i.e. links that don't exist in any websites, but that exist because of the behavior of users. The web should be sensitive to hysteresis; i.e. the order and context in which web pages are viewed. Word2Vec, markov chains, and other methods show us that the position of items relative to other items is important in defining its importance, context, and meaning. The web should be able to help you infer what pages to view next. What web pages were not useful.

The web should be able to identify where information is duplicated and identify it's original source. One should be able to query back-links -- i.e. when I'm on a page, what are all pages that link to this page? Where do most people come from who land on this page? The web should learn from how (many) people query/search and traverse pages, and supplement their experience by having a concept of "sequences" where searchers can be shown a map / paths others took.

If google analytics is useful to site administrators, it's almost certainly also integral to the user/browser's experience. And these relationships should be surfaced more transparently to the end-user in ways that are value-add and actionable.

End-users should be able to tune and cultivate their web -- they should be able to tag/label/associate web pages via first-class annotations (at the protocol level, not by a service like twitter or google) and publish these as their "webs" which can be queried. This will of course suffer from the same Wikipedia-style editing and curation complications.

So many of the features we enjoy within the silos of services -- the ability to review, the like, to comment, to recommend / share / @mention, to suggest an edit, to label or tag, to connect... Should be first-class citizens of a web we all enjoy. And the web should embrace these primitives, be reactive and responsive to to our contributions, and grow with us.

The web can be so much more.

---

inb4 decentralized web.

I'm a big fan of decentralization. I've been intimately working w/ folks in the field for 6 years. Some of these issues may be assuaged by thoughtfully designed decentralized protocols. It's how we succeeded in making the web (DNS, Routing).

But please resist from respond to this thread with "decentralized web" like it's a silver bullet to these problems. This is a misuse of the label which conflates the notion of "decentralization" as an ideological stand-in for "freedom" when there are many improvements the web needs which are in no way contingent on decentralization.

- The vast majority of content no-one is incentivized to save. It's not valuable until it is -- and that's an economic bet most people are not willing to take. This is why non-profit efforts like the Internet Archive's Wayback Machine exists. And why Google (who is in the business) doesn't have a competing service (outside a limited collection of caches).

- One should ask, why problem is decentralization solving, if there isn't already a centralized solution? The big perception is that unifying decentralization frameworks will offer organized censorship-resistance and freedom from corporate interests. Technically maybe. But the problem of search and discovery is fundamentally one of centralization. Even federated services in such a system will be incentivized to compete for the attention of patrons.

- Decentralization misses out on economy of scale. The biggest players in a decentralized network will still be Amazon, Google, and other big players (who run the networks).

- People talk about decentralization at too-broad a scale to be useful in solving the problems above, which don't yet have good centralized solutions.

- The web is in may ways already decentralized. It consists of hundreds of millions of servers, domains, name-servers, and services. The *problem* is that no one discovers most of them.

- There are all sorts of challenges emerge e.g. revenge-porn, elicit material, etc. which emerge with the ideal of "censorship resistance". And there aren't great solutions to these yet.

- A decentralized protocol may be very useful in making sure (a) content doesn't link rot (b) is backed up in multiple locations (c) content is usefully version controlled and content-addressable (d) content is made more geographically available / performant, etc.

On Skepticism of the Decentralized Silver Bullet:

I wrote an essay a few months back called, "On Modern Digital-Warfare" which was catalyzed by a conversation I had with with a friend where we were commenting on how many of today's technologists are building protocols as a cover to subvert existing systems; to find unregulated loopholes through which their ideologies can be virally deployed/installed to reach the masses [as a means of a coup d'etat].

The general premise is, 30 years ago, if you disagreed with policy, you would apply political pressure (elect officials, support bills, rally), you'd participate in unions or organize strikes, you'd go to war.

Many of these vectors have become untenable, less attractive, or obviated because (a) modern day political America is second wheel to the corporate vehicle on which they rely for (lobbied) financial support, (b) technology companies evolve with their exploits faster than the government's pen-and-paper process can learn and respond to them, (c) technology provides both institutions and corporations a way to wage [attention] war which is both far faster and farther reaching than traditional government process and also less directly violent/oppressive (there's plausible deniability that anything bad is happening because it's all indirect -- most people will think it conspiracy theory, and this is an advantage of the medium of attack).

When VCs dump billions of dollars into ICOs, blockchain technologies, etc, what they're really betting on / investing in is the quality/definition of blockchain which makes it ubiquitous and pervasive. They want the opportunity to monopolize the next "web" -- our public roads, our hospitals, our telephone service, our water rights. Whatever the things [commons] are which we fervently protect because they should be human rights / public utilities, capitalists see as their greatest opportunity to supplant under the coup of a new technology, to monopolize in a way the government cannot defend/regulate against, and to effectively make decisions without the checks and balances of government.

I think many of us long for a world where a government ecosystem may exist which evolves as quickly as corporations. And I think we know that such a future requires technological advancements, such as "decentralized ledgers of consensus". But from my vantage point, when I project even the most promising projects 10 years into the future, I see bleak outcomes driven by the reality that there are more myopic technologists and wealthy people hiring myopic technologists pushing forward self-serving agenda than there are technically literate freedom fighters who understand both how to effectively employ technology as well as the sensitivities around policy and technical/digital warfare.

Right now we're in an age where millions of technically literate coders have digital atom bombs, and most of them just want to get rich and win the game. We're proposing a solution to defeat the "other team" [corporate interest] by giving everyone hydrogen bombs.

This essay is a followup to...

- This optimistic piece entitled: "The Future is Smalltalk"

- This pessemistic piece entitled: "On the Fall of the Commons"

- On Modern Digital-Warfare: https://www.facebook.com/michael.karpeles/posts/10103483448772600

- See also: On Indirection & the Implications of Moral Profiteering https://www.facebook.com/michael.karpeles/posts/10102911316939380

Healthy Reservations about Decentralization

In a few important ways, I’m a cynic of decentralization and technology as a silver bullet. And I think this is a healthy perspective because we’re still in the early days. That doesn’t mean I don’t think it will succeed, or that it shouldn’t succeed. Only that I see efforts like cryptocurrency as the rollercoasters they are — there’s billions of dollars out there and plenty of incentive for capitalists to collude to game the system, numerous ways governments can impose unsavory regulations, security vulnerabilities which have yet to be discovered, and issues around scaling and efficiency which still need to be revealed and addressed. And when these efforts go wrong, or groups which are highly organized and funded step in to undermine a new effort, it can cause a lot of damage.

I think we're still missing an critical component to adoption, defensibility, and sustainability, and that's education. Many of these systems are being designed in myopic bubbles and are rapidly being presented to people who don't understand the consequences of the technology. My personal philosophy is to not invest in things I don’t understand well, and not to invest more than I can afford to lose and I feel like perhaps too many people are shooting for the moon with bitcoin and other coins. And maybe they’ll win the bet, but it’s strange to think major financial infrastructure is being built over top of these bets. Without education, there's also the issue of hype. Investory dump money into anything with the name blockchain, AI, or crypto-currency because their top priority is investing in a technology which has the potential to spread massively, like a virus. And I think this type of strategy undermines a lot of legitimate efforts and risks creating things which are indeed a lot like viruses.

I don’t want to be too cynical — hopefully just the right amount of cynical. And right now I think we’re still in a proving and experimenting phase, of what stands to be a really important transition for the world, if done right.

Can I share a short story?

Stripe

I remember when John Collison first showed me Stripe.com at the Noisebridge hackerspace in San Francisco.

He was able initiate a payment on my credit card using an http curl. I think this woke me up to the idea that in an ideal world, payments could be done instantly using APIs and maybe didn’t require huge amount of middleware. I also so how much fraud Stripe had to deal with, and PayPal as well — that’s a huge part of the value they add. And so I get the feeling special protocols, or otherwise centralized trust institutions, will still be necessary in the future of the decentralized web.

In short, there will always be risks, and we would do well to Curb our Enthusiasm. But we should also keep trying.

Centralization, Decentralization & Re-Centralization- Breaking the Cycle

This title was retroactively taken from Cory Doctrow's Decentralized Web Summit 2018 round table.

A strange thing about the web is, in many ways it's always been a decentralized system. Organizations like Google and Facebook have actually had a heck of a time centralizing it.

We have 3B+ people[1] with internet access, each with their own brain, each thinking of ideas separately, taking notes separately, sometimes even across several different programs (google docs, evernote, etherpad, github, facebook, email). You likely have thought before, "Shoot, I've stumbled across some excellent resources on the web which are buried" or "I can't believe this idea was discovered 20 years ago". The fact is, the web (and pretty much no system) is not set up to be centralized (for instance, there's no single source of trust for authentication/identity, no single source of all academic papers in the world, and no entity resolution or algorithm to perfectly maintain a record/index of all the services even which try to address these centralization efforts!)

Don't get me wrong, decentralization has many favorable qualities. It can offer a strategy for a degree fault tolerance and permanence, discourage monopolization, and can provide efficient dispatch, computation, and retrieval of (especially too large for an individual commodity machine) tasks/data which are well suited for parallel computation or which can benefit from spatial and or temporal locality.

But the most important element of decentralization is that it decentralizes something meant to be centralized (by definition). And this requires, by necessity of definition, that we indeed have a solution for how centralization is achieved. And if you ask me, we're not especially good at this. Again, the Economy, politics/voting, authentication as examples.

Why is it imperative to address this today? Because, we're creating more and more data, but our mechanisms for improving the web (as a protocol) are not keeping up. Right now, Google (and several other "indexing search engines") are retroactively turning a distributed system into a centralized one by running imperfect algorithms over all documents in the web. This is partly an issue of trust -- Google et al. do this because people are afraid that there should be any single institution physically capable of monopolizing an index of the web (I say physically as opposed to practically as Google eta al. do practically control this -- just not to the mutual exclusion of any other party).

Thus, today there is no perfect ledger of all existing documents (other than these artificially produced, imperfect ones). The obvious solution (which is not so obvious to implement and get adopted) is building "decentralized" centralization into the protocol-level itself. That is, for decentralized agents (necessitated by the logistic enormity of the task) to maintain a centralized ledger, at a protocol level. IPFS (https://ipfs.io) is one interesting attempt to achieve this. Bitcoin and Ethereum are interesting approaches as well, which not only replace a middleware, but also provide a more comprehensive real-time solution.

The question remains, even with a framework of decentralization to power a the centralized solution we need, how do we incentive innovation of this framework (e.g. Filecoin; http://filecoin.io/) and what might a decentralized-centralized web look like or enable us to accomplish? Imagine if there was a single note taking database for the whole world. And as you type a note, the service compares and entity resolves (matches) your note against every other note in this universal database. You see an auto-complete dropdown box, just like when you're tagging someone in facebook, and it allows you to link your idea or add your ideas to an existing record. Instead of Google trying to reverse engineer search engine result pages, we'd have a real web of knowledge. All original ideas and notes would exist only once, people would spend less time seeing what's been done, and spending more time adding value to the universal graph.

Of course a lot has to happen (and other infrastructure is required) before this vision becomes a reality, but it's achievable in our life time. A real universalized, decentralized-centralized framework / index, not owned by any one person; a single stream of consciousness of all worldly knowledge, accessible to all.

P.S. I am attempting to build something like this (but only for my blog) to allow me to register ideas, notes, todo items in a universal database. I will be the first to gladly admit Mark Carranza has had this built[2] and has been using it for himself for *years*, and only today did I really understand its full potential (though I know there are things he wishes it had, like better semantic tagging, todo functionality, and an API into other service -- some of which he may have added since we last spoke) which will be fun to work on.

cc: Mark P Xu Neyer, Bram Cohen, Bob Ippolito, Brent Goldman, Juan Batiz-Benet, Stephen Balaban, Drew Winget, Gregory Price, Bernat Fortet Unanue, Akhil Aryan, Jan Paul Posma, Michael Noveck

EDIT (adding citations):

[1] statista.com/statistics/273018/number-of-internet-users-worldwide [2] http://quantifiedself.com/2009/09/the-social-memex/